By Srishti Sangwan | Reality Check

India is a land of linguistic diversity—122 major languages, over 1,500 minor ones, and an education system that tries to juggle them all. Enter the Three Language Formula (TLF)—a policy crafted in the 1960s that aimed to unify the nation through multilingual education. At first glance, it seems like a well-balanced recipe for harmony: learn your mother tongue, Hindi, and English (or another Indian language).

But dig a little deeper, and it becomes clear that this idealistic formula might be more of a patchwork than a plan. In this post, we break down what the TLF was supposed to do, why it hasn’t really worked, and what NEP 2020 is trying to do about it.

📚 What Is the Three Language Formula?

First introduced in the 1968 National Policy on Education, the TLF aimed to promote:

Cultural identity through the mother tongue or regional language. National integration by teaching Hindi. Global relevance via English.

The basic idea was:

👉 First language – Mother tongue or regional language

👉 Second language – Hindi (for non-Hindi speakers) or a modern Indian language

👉 Third language – English or another Indian language not studied yet

Sounds fair, right? In theory, yes. In practice? Not so much.

❌ Where It All Goes Wrong

1. The North-South Tug-of-War

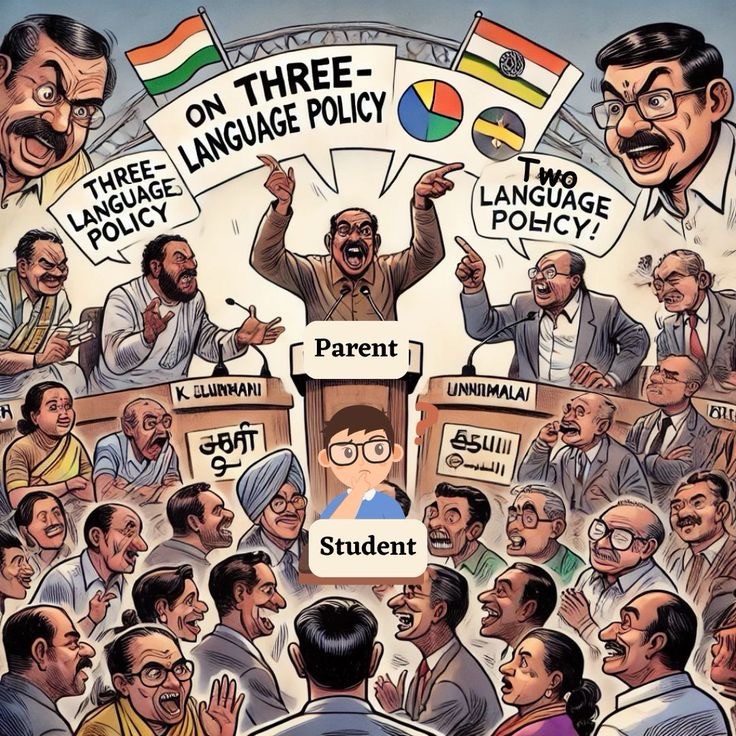

The biggest challenge? Imposition of Hindi. States like Tamil Nadu outright rejected the TLF, opting for a two-language formula instead. For them, promoting Hindi felt like a cultural imposition by the North. Language became a battlefield rather than a bridge.

2. Infrastructure Gap

Many rural schools can barely manage one qualified language teacher—let alone three. This leads to poor implementation. Often, the third language is taught like a subject to pass, not a language to use.

3. The Language Hierarchy Problem

Let’s be honest: in most Indian schools, English reigns supreme. Parents want it, students chase it, and jobs demand it. Hindi and regional languages, although mandatory, are often seen as less “useful.” Instead of promoting equality, the TLF has unintentionally created a language caste system.

4. Overburdening the Learner

Imagine being a 10-year-old trying to decode three very different scripts, vocabularies, and grammar systems—without adequate support. For many students, especially in government schools, this leads to surface-level learning and sometimes even disinterest or dropout.

🔍 The Politics of Language

The TLF doesn’t just deal with education—it plays directly into the politics of language, identity, and power. Promoting Hindi as a “link language” privileges Hindi-speaking states. English, ironically a colonial language, now opens doors to social mobility and global access. And where are the tribal or endangered languages in this equation? Barely visible.

So, while the policy claims to protect linguistic diversity, it often ends up marginalizing the very communities it aims to include.

🧾 Enter NEP 2020: Same Wine, New Bottle?

The National Education Policy 2020 reaffirms the TLF but adds a new twist:

“Wherever possible, the medium of instruction until at least Grade 5 will be the mother tongue or local language.”

Nice idea, but let’s ask a few real questions:

Where are the trained teachers for this? Will regional-language-educated students survive in an English-dominated higher education system? Are we widening the urban-rural gap even further?

Without concrete implementation plans, this reform might remain just that—a reform on paper.

🧠 So, What’s the Way Forward?

If we’re serious about multilingualism and inclusive education, here’s what needs to happen:

✅ Flexibility: Let states and schools choose the most relevant third language—don’t make it a top-down imposition.

✅ Invest in Teacher Training: Three languages require more than enthusiasm—they need qualified teachers and resources.

✅ Empower Indigenous Voices: Include tribal and endangered languages in school curriculums meaningfully.

✅ Focus on Functional Multilingualism: Don’t teach languages for marks—teach them to communicate, create, and connect.

✍️ Final Thoughts

The Three Language Formula started as a noble idea—but like many policies, it suffers from uneven implementation, regional tensions, and a disconnect from ground realities. It’s time we stopped treating language as a checkbox on a policy document and started treating it as what it really is: a lifeline for identity, learning, and opportunity.

If India wants to stay true to its linguistic heritage and democratic ideals, our language policies must go beyond symbolism and dive deep into equity, access, and authenticity.

🔗 What do you think about the Three Language Formula? Drop your thoughts in the comments or share your regional language experience with us.

📢 Follow Reality Check for more honest takes on education, policy, and the ground realities that rarely make headlines.

Leave a comment