Cheating — in relationships, education, sports, or professional life — is a global phenomenon. People from all walks of life, regardless of age, culture, or status, have either committed, experienced, or witnessed it. But what makes someone cheat? Is it merely a lack of morals, or are there deeper, often hidden factors behind such behavior?

This article explores the psychology of cheating through both individual and systemic lenses, drawing upon behavioral research and real-world observations.

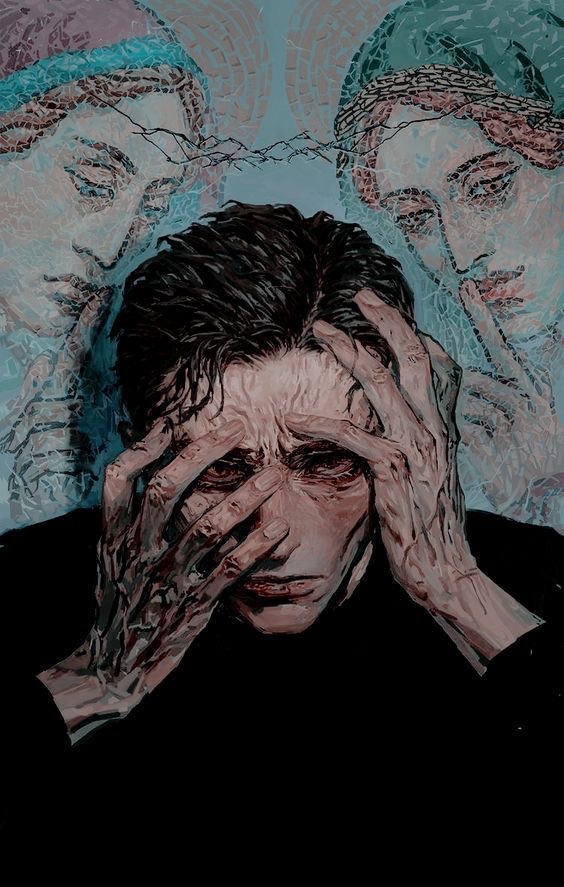

🔹 1. The Psychology of Self-Deception

One of the most significant reasons people cheat is the ability to rationalize their dishonest behavior without damaging their self-image. As behavioral economist Dan Ariely and colleagues note in their research, most people want to benefit from cheating — but only to the extent that they can still view themselves as good, honest individuals.

“People don’t need to be convinced to cheat. They need to be given a reason to think it’s okay.”

— Ariely, D. (2012). The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty

This is known as self-concept maintenance — the idea that people balance the gains of dishonesty with the need to maintain a positive view of themselves. Small acts of cheating are often seen as “harmless” and thus more easily justified.

🔹 2. Pressure to Succeed

Academic, professional, or social pressures can drive individuals to cheat when the fear of failure becomes overwhelming. In their landmark study on academic dishonesty, McCabe, Butterfield, and Treviño argue that institutional culture and peer behavior significantly influence a student’s decision to cheat.

“When students believe their peers are cheating, they are more likely to engage in the same behavior themselves.”

— McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in College

The same applies in workplaces or relationships — when people believe everyone else is cutting corners, infidelity or dishonesty starts to feel justified or even necessary for survival.

🔹 3. Opportunity and Lack of Supervision

People are more likely to cheat when they think they won’t get caught. Loopholes, lack of surveillance, or weak systems increase the temptation to bend the rules. Digital environments especially offer anonymity, making deception easier and consequences less immediate.

🔹 4. Emotional Disconnection and Unmet Needs

In romantic contexts, cheating is often not just about desire or impulse, but about unmet emotional needs. When communication breaks down or one feels undervalued, people may seek validation elsewhere. This kind of cheating often stems from emotional neglect rather than calculated betrayal.

🔹 5. Cultural and Social Norms

In some cultures, the line between success and integrity is often blurred. When societal values overemphasize achievement over process, people are more likely to cheat. This is especially true in hyper-competitive environments like entrance exams or corporate performance reviews, where only outcomes matter.

🔹 Conclusion: Cheating Is a Symptom, Not Just a Choice

Cheating is not just about flawed character; it’s a reflection of internal conflict, external pressure, and societal conditioning. While it should not be excused, it must be understood. Rather than only asking “Why did they cheat?”, we must also ask “What systems made cheating seem like the only option?”

Understanding the psychology of cheating helps build a culture that promotes integrity — not through fear of punishment, but through empathy, fairness, and trust.

References

1. Ariely, D. (2012). The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone—Especially Ourselves. HarperCollins.

2. McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Treviño, L. K. (2012). Cheating in College: Why Students Do It and What Educators Can Do About It. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Leave a comment